In the quiet countryside of Hugo, Oklahoma, a farmhouse stands as a testament to grit, ingenuity, and endurance. Built in 1915 on hand-hewn Bois D’Arc beams, this home has witnessed more than a century of seasons, families, and progress. Its story is more than just about wood and nails—it’s about the people who made their lives here, the history of Choctaw County, and the fascinating journey of land ownership from Indian Territory to the hands of American citizens. Recently purchased by new stewards of the land, this farmstead includes the first operational windmill in Choctaw County, a symbol of resilience and innovation in an era before modern conveniences.

Building a Home in 1915

Imagine Oklahoma in the early 20th century. The land was fertile, the communities were small, and the conveniences we take for granted today—electricity, running water, power tools—were luxuries still decades away for rural families. To build a home in 1915 required more than ambition; it required the strength of both humans and animals.

The massive Bois D’Arc beams that still hold this farmhouse together were likely hauled into place by mule teams. With no mechanical lifts or cranes, settlers leveled and aligned each timber by hand, relying on precision and patience. Bois D’Arc, sometimes called “Osage Orange,” was prized for its strength and resistance to rot. Farmers knew that a home built on these beams would stand strong for generations. Over one hundred years later, that prediction has proven true. The structure remains solid, a living monument to the craftsmanship and perseverance of its builders.

Bois D Arc Beams Hold this house up.

The First Windmill in Choctaw County

This farmhouse is also remembered for hosting the very first operational windmill in Choctaw County. In a land where self-sufficiency was vital, a windmill was revolutionary. It harnessed nature’s power to pump water, sparing families the backbreaking work of hauling buckets from streams or wells.

Today, we may see a windmill as a quaint symbol of country living, but in 1915 it represented cutting-edge technology. The arrival of a working windmill on this property marked a turning point for local farmers, setting an example of how innovation could ease daily burdens and improve productivity. For the families who lived here, the windmill meant more than just water—it meant progress, security, and hope.

A Look at the Property Today

According to its recent listing, the farmhouse sits on 104.9 acres of pasture and woodland, offering a blend of open space, grazing land, and timber. With barns, sheds, and wide-open fields, it’s a true working farmstead, well-suited for cattle, horses, or crop production. The sheer scale of the land gives its new owners room to grow, dream, and build on a foundation more than a century old.

Inside, the home reflects both its age and its resilience. With thoughtful updates and restoration, it is ready to provide shelter and comfort for another hundred years.

The buyers of this property are not just homeowners—they are caretakers of history. Their purchase ensures that the story of this farmhouse, its beams, and its windmill will continue for generations. A special thanks goes to Anitra Babcock for her excellent work in representing the property and representing the sellers on the transaction. Congratulations to the new owners on their very own piece of Oklahoma history.

ALLOTMENT PATENT.

No 11228

185

Choctaw by blood. ROLL No, 4328

DATE OF CERTIFICATE. October 25, 1204.

THE CHOCTAW AND CHICKASAW NATIONS, INDIAN TERRITORY.

From Indian Territory to Private Farm

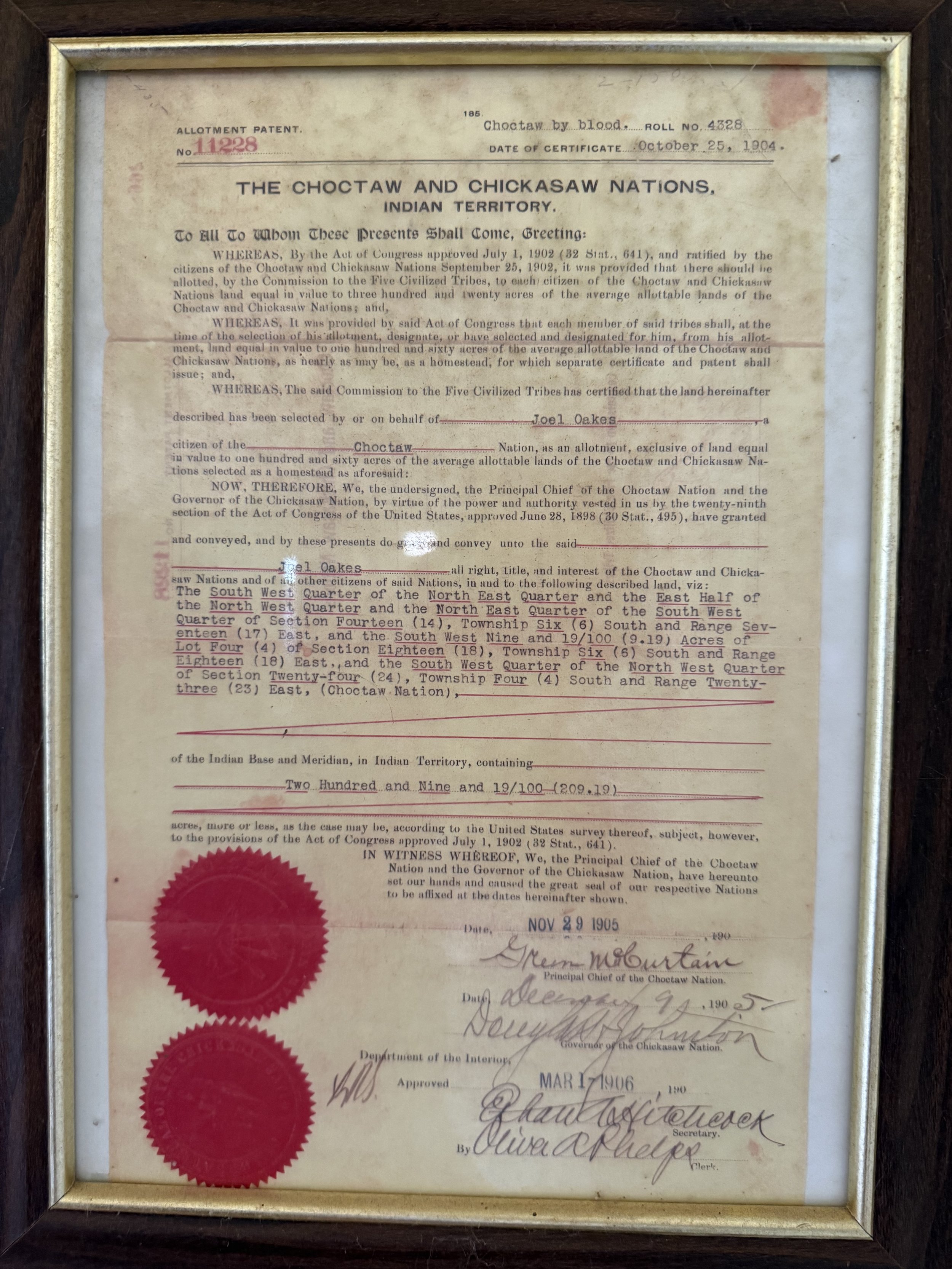

What makes this farmhouse even more fascinating is its connection to the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations. The framed document you see above is an allotment patent—a legal record of how land once held collectively by Native Nations was transferred into private ownership under U.S. law.

What Is a Land Patent?

A land patent is the first official transfer of title from the federal government to an individual. Before mortgages, deeds, or modern title companies, the land patent was the foundational legal document that proved ownership. Once a patent was issued, that property could be sold, inherited, or developed by the owner.

The patent in this case was issued in 1904 under the authority of the Dawes Act and related agreements with the Five Civilized Tribes. The Dawes Act sought to divide communal tribal lands into individual allotments, with the stated goal of encouraging farming and assimilation. In practice, it led to millions of acres of “surplus” lands being opened up to non-Native settlers.

For the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations, the process was overseen by federal agents who recorded each citizen’s name, tribal roll number, and assigned acreage. The patent in the photo was issued to Joel Oakes, a Choctaw by blood, as his legal allotment. Over time, through sale or inheritance, that land became part of the patchwork of private farms that make up Choctaw County today—including the site of this 1915 farmhouse.

From Territory to Statehood

At the time this patent was issued, Oklahoma was not yet a state. It was Indian Territory, home to members of the Five Civilized Tribes who had been forcibly relocated along the Trail of Tears in the 1830s. When Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907, much of the land had already passed into private ownership through patents like this one.

This history is a reminder that every farm, every town, and every home in this region sits on land that once belonged collectively to tribal nations. While the allotment system is controversial in hindsight, the patents themselves remain vital historical records. They link present-day families to the earliest days of statehood and the often complicated legacy of land in Indian Territory.

The Endurance of Place

Standing before this farmhouse today, it is impossible not to feel the weight of history. The Bois D’Arc beams tell a story of human determination. The windmill tells a story of innovation. The land patent tells a story of transition, from Indian Territory to statehood, from communal land to private farm.

Yet perhaps the most powerful story is the one that continues. More than a century after the first family built this home, a new family begins their own chapter here. They inherit not only a house but a legacy—one that stretches from tribal land allotments to the first windmill to the promise of another hundred years.

Conclusion

Historic homes like this farmhouse in Hugo, Oklahoma, remind us that real estate is more than square footage and property lines. It is about people—those who came before, those who endured hardship, and those who continue to dream. This 1915 farmstead stands as living proof that with determination, strong beams, and a little wind at your back, you can build something that lasts.

To Anitra Babcock, thank you for preserving and sharing this story. To the new buyers, congratulations on your new farmstead. You now hold not only a deed but a piece of Choctaw County’s enduring legacy. May the farmhouse stand strong for another hundred years, and may the wind that once turned its blades continue to whisper stories across the fields of Oklahoma.

Happy Clients on Closing Day!